How the Kulea Watoto Project is Reimagining Early Childhood for Refugee Families in Uganda

How the Kulea Watoto Project is Reimagining Early Childhood for Refugee Families in Uganda

Shafique Ssekalala, Programme Director at Madrasa Early Childhood Programme Uganda (MECPU), during an interview.

“When the refugees come, they come with children.” This simple statement by Shafique Ssekalala, Programme Director at Madrasa Early Childhood Programme Uganda (MECPU), reflects a sobering reality: emergencies do not just displace adults. They interrupt entire childhoods. Uganda is home to over 1.5 million refugees, many of whom have fled conflict in neighboring countries. Nearly 40 percent of these refugees are children under the age of 14. Yet most refugee children, particularly those below age eight, are unable to access safe, supportive early childhood development (ECD) services. Government and sector reports estimate that fewer than 30 percent of refugee children aged zero to eight are enrolled in any form of organized early learning. Families often face multiple, overlapping challenges such as food insecurity, economic instability, trauma, and poor access to healthcare. Without targeted support during the early years, children’s long-term learning, health, and wellbeing are put at risk.

To respond to these gaps, the Kulea Watoto project, Swahili for “nurturing children” was launched in 2023. Led by the Madrasa Early Childhood Programme in partnership with organizations including the International Rescue Committee (IRC), AfriChild, Literacy and Adult Basic Education (LABE), and Kabarole Research and Resource Centre (KRC), the initiative works in both urban and rural refugee-hosting areas, including Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA) divisions of Rubaga, Makindye and Central including settlements in Yumbe and Kyegegwa districts.

The project employs a two-generation approach that aims to improve children’s development while supporting caregiver wellbeing. As a national leader in ECD with over three decades of experience, Ssekalala helped shape this model to reflect Uganda’s evolving refugee context. He explains that ECD services cannot succeed unless families are supported as a whole.

“The reality is that you cannot nurture a child without nurturing the caregiver,” says Ssekalala. “Our work strengthens early learning while improving household livelihoods, because the two are connected.”

A Two-Generation Model to Meet Family Needs

Under the project’s two-generation model, caregivers receive business training, mentorship, and seed funding to start small enterprises. These include vegetable stalls, snack vending, tailoring, and other low-capital ventures. Each participant receives startup support of about 800,000 Ugandan shillings.

More than 300 families have so far benefited from these grants. Six-month progress tracking has shown household income growth of up to 30 percent, enabling families to meet basic needs such as food, rent, and school fees.

Scovia Kyalisima prepares merchandise at her business stall in Nsambya, Makindye division. This business was established with funding from the Kulea Watoto Project.

“When caregivers feel stable, they become more engaged in their children’s growth and learning,” says Ssekalala. “We have seen this play out in the home and in the classroom.”

This connection between financial wellbeing and parenting capacity is a core part of the project design. Kulea Watoto integrates economic empowerment with parenting sessions, early stimulation activities, and ongoing follow-up by community mentors. In households previously marked by stress and disengagement, caregivers are now creating more nurturing environments for their children.

Early Learning Quality and Access

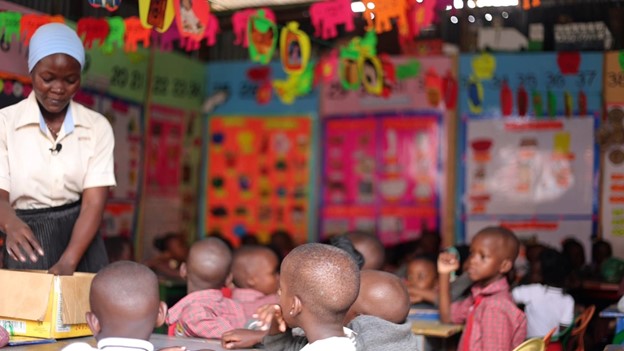

Another pillar of Kulea Watoto is strengthening the quality of existing early learning spaces. Many refugee-serving ECD centers operate with limited resources and few trained caregivers. Classrooms are often overcrowded, and teaching methods tend to rely on rote instruction with little attention to play, stimulation, or emotional development.

Through the project, over 50 centers have received support. Teachers are enrolled in foundational courses on child-centered teaching, inclusive practices, and psychosocial support. In addition, peer mentor networks and refresher workshops offer continued learning, giving teachers the confidence and tools to create engaging classrooms.

“At the start, some teachers lacked formal training, and centers were quiet and rigid,” says Ssekalala. “Now classrooms are lively, children are active, and learning happens through songs, stories, and games.”

Jauharah Mwesigwa, a lead caregiver at Shiperoy Nursery and Primary School in Lukuli, Makindye division, attends to her learners during a class session.

Community engagement has also improved. Parents are more involved in their children’s education and contribute ideas and feedback through parent meetings and center management committees.

Building Skills Through Play at the Household Level

Kulea Watoto also supports play-based learning within homes. Village Health Teams (VHTs), already trusted community actors, are trained to coach caregivers on early stimulation techniques. They demonstrate how to use everyday materials such as plastic cups, sticks, or cloth scraps for games that build children’s thinking and social skills.

Play is framed as essential, not optional. VHTs emphasize that intentional interaction helps children build vocabulary, emotional regulation, and motor coordination, even in low-resource settings.

“We show parents that play is learning,” Ssekalala explains. “You do not need expensive toys. What matters is how you talk, engage, and respond to your child.”

To date, over 150 VHTs have received training and have reached hundreds of households. Sessions cover topics such as positive discipline, child protection, and how to create safe play environments. Follow-up visits help reinforce key messages and build caregiver confidence.

Margaret Nakavuma Kisakye, a trained Village Health Team (VHT) member, interacts with the children during her routine visit to homes in Nsambya, Makindye division.

Evidence-Driven Design and Learning

Throughout implementation, the project uses data to adapt its methods. Baseline studies captured caregiver stress levels, children’s nutrition status, and early learning participation. Periodic reviews track changes in income, developmental outcomes, and service satisfaction.

Ssekalala emphasizes the value of this learning loop. “Feedback helps us adjust. When we saw that some caregivers needed more help managing business records, we added bookkeeping sessions. When teachers asked for more training on handling trauma, we adapted our content.”

In one Kampala center, for example, teacher mentors worked with a caregiver whose child had become withdrawn. Through joint visits, they introduced emotional check-ins and story-based learning. Within weeks, the child began participating more actively in class.

These real-time adjustments, guided by frontline feedback and community voices, ensure the project stays grounded and relevant.

Sustainability Through Local Systems

Kulea Watoto also focuses on building local ownership. The project collaborates closely with district education and health offices, and aligns its interventions with Uganda’s National ECD Policy and local government strategies.

Materials and curricula are shared with public institutions, and capacity-building efforts target local trainers, VHTs, and education officials who can carry the work forward. ECD center leaders are trained in budgeting, resource management, and inclusive governance.

Ssekalala sees this as essential to long-term impact. “We cannot work in parallel to government. Our aim is to strengthen systems so that these changes can last.”

Early Results and Pathways Forward

While full evaluations are ongoing, the project is already seeing promising results. Enrollment in supported centers has increased. Caregiver confidence has grown. Children are demonstrating improved social-emotional skills and greater readiness for primary school.

Perhaps most importantly, communities are beginning to see ECD not as a luxury, but as a shared responsibility.

“Refugee children have the same potential as any child in Uganda,” Ssekalala says. “With the right support, they can thrive. We are not just building services, we are building belief in the importance of early childhood.”

Children play at one of the play spaces established by the Kulea Watoto Project in Konge, Makindye Division.

The project consortium aims to scale up its model and share learnings across the humanitarian and development sectors. Ssekalala believes the lessons from Kulea Watoto could help transform how refugee early learning is approached in Uganda and beyond.

“When we invest early, we invest in the future,” he says. “These children carry with them the strength of two worlds. Let us give them the tools to flourish.”