How Local Leadership Is Strengthening Uganda’s Early Childhood Systems

How Local Leadership Is Strengthening Uganda’s Early Childhood Systems

Florence Kyoshabire, Education Supervisor - Rubaga Division under the Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA), during an interview.

Uganda is home to one of the youngest populations in the world, with over 50.5% of its citizens under the age of 18. Yet, access to quality early childhood education remains a persistent challenge. Fewer than 30% of children aged 3 to 5 are enrolled in an Early Childhood Development (ECD) centre. For refugee and vulnerable families, the numbers are even lower. Many children begin primary school without the foundational skills needed to thrive, and thousands of caregivers remain unsupported, caught between the demands of survival and the developmental needs of their children.

In this context, the Kulea Watoto project is striving to strengthen early childhood systems by supporting both the child and the caregiver. In Rubaga Division, that vision is being carried forward by local government leaders. Florence Kyoshabire, the Education Supervisor under Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA), is helping to integrate the project into the city systems in meaningful and lasting ways.

Kyoshabire began her involvement with Kulea Watoto in 2023 when KCCA was engaged as a key government partner.

“As a supervisor, I was brought on board to ensure that the project was rooted in our existing structures, particularly around early childhood,” she explains. “Our mandate at KCCA is to support equitable, quality education. Kulea Watoto came in to complement that.”

Working within ECD policy

According to Kyoshabire, the project aligns with Uganda’s broader development framework.

“It fits within our national policies on both early childhood and livelihoods. The National Integrated ECD Policy encourages partnerships across sectors; health, education, community development. That is what Kulea Watoto is doing. It brings these sectors together to support families holistically, especially in urban and refugee-hosting divisions like Rubaga.”

The project’s two-generation model is particularly relevant in a city context, where caregivers often face multiple stressors. “You cannot work with the child and forget the parent,” Kyoshabire notes. “The economic empowerment component, where caregivers are trained and linked to livelihood opportunities, supports school readiness and improves attendance at ECD centres. It reduces dropout and absenteeism, because families have more stability at home.”

She adds that this support has had ripple effects. Caregivers who were previously disengaged are now more involved in their children’s learning. “They attend sessions, they ask questions, and they follow through at home. That sense of ownership and confidence is one of the most powerful outcomes of this project.”

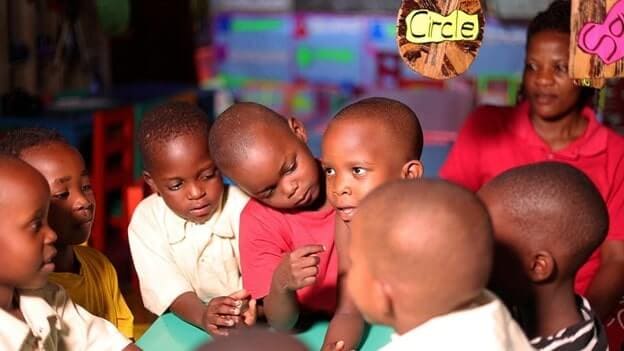

Children at Kiti Nursery School in Katwe, Kampala Central, interacting in class as a parent looks on.

Effective Training and mentorship

On the technical side, Kyoshabire highlights the importance of training and mentorship.

“Government staff, caregivers, and local leaders in Rubaga have benefited from regular coaching and hands-on support. The CCD training for our Village Health Teams and community workers has had real impact. They are more confident when talking to parents, encouraging play, and supporting early stimulation.”

She emphasizes that the materials and tools shared through the project have made a visible difference.

“Caregiver guides, play-based learning resources, and visual aids are now being used across our centres. That technical support helps us bridge knowledge gaps and apply good practice in real-world conditions. Even caregivers with limited formal education are now implementing what they learn.”

Integration into existing structures has been a key focus area from the start. “We have deliberately worked to make sure that schools, caregivers, and local leaders are part of the process. Center Management Committees now include focal persons from KCCA. This approach strengthens local governance and increases accountability,” says Kyoshabire.

Looking ahead, she believes sustainability will depend on this kind of integration. “As donor support gradually reduces, what remains are the structures, the knowledge, and the community networks we have built together. That is why we are working on embedding some of the project components—like the caregiver training—into KCCA’s broader ECD strategy.”

Florence Kyoshabire, Education Supervisor - Rubaga Division under the Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA), during an interview.

Keeping up the momentum

Kyoshabire shares that discussions are already underway to adopt certain tools and practices from Kulea Watoto at scale. “We are reviewing the materials and adapting them for use in other divisions. It is a step-by-step process, but we are committed to maintaining the momentum.”

When asked what she values most about Kulea Watoto, Kyoshabire is reflective.

“It is the way they work with communities. They do not come with fixed solutions. They listen. They co-create. And that is what makes their approach sustainable. They are building with us, not for us.”

She recalls a centre in Rubaga that had previously struggled to attract children due to poor conditions and lack of parent engagement. “Today, that same centre has a structured timetable that includes play and stimulation. Caregivers are using visual aids and activity cards. Parents show up for sessions. That is transformation. And it started with listening, with building trust.”

As Rubaga Division continues to adapt and strengthen its ECD systems, Kyoshabire remains committed to championing early learning from within the government. “We’ve seen what works. Now we must continue investing in it. Early childhood is not just the foundation for school, it is the foundation for life.”